THE DANES, NORMANS AND “FRENCH” CANADIANS

The Danes

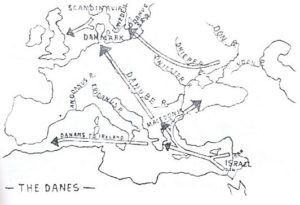

The Danes or Norsemen who invaded and settled in north-eastern England and part of Scotland in the ninth and tenth centuries, as well as their kinsmen who remained in Scandinavia (Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Iceland), are another part of our race whose name and traditions bear witness to their Israelitish origin.

In considering this identification of the Danes, we should note that their coming into Britain was not the invasion of a foreign or alien race. On the contrary, they were very closely related to the Saxons, being in fact a northern branch of that people. This, in itself, identifies the Danes as Israelites for the evidence previously presented proving the Israelitish origin of the Saxons must, therefore, apply also to the Danes.

Further, the ancient Danish (Norse) traditions claim that the Danes are the descendants and followers of a great leader named Dan who lived sometime previous to 1,000 B.C. This is important for, in the history of the ancient world the only man named Dan who became the father and head of a tribe or people of that name was Dan, the fifth son of Jacob-Israel, from whom is descended the Israelitish Tribe of Dan.

The history of the Tribe of Dan also offers important evidence. First, we should note that during the forty years of wandering after the Exodus, a part of this tribe broke away from the main body of Israel and established itself in the north-eastern part of Palestine, calling it Phoenicia. It is interesting to note that the ancient Danish (Norse) alphabet, the Runic, resembles the Phoenician and is generally considered to have been derived from it.

Then we should note the geographical location of the Danites after Israel settled in Palestine. Their first allotment of land, which was on the west coast, was found to be too small and part of the tribe was given another portion in the extreme north of the country. This grant included most of Phoenicia, which had previously been settled by a part of their own tribe. The importance of this lies in the fact that Palestine’s three important seaports were in the territory of the Danites (Joppa in South Dan, and Tyre and Sidon in North Dan).

Thus it is that the Danites, including the Phoenicians, became the merchant seamen and the commercial traders, not only of Israel, but of the whole ancient world, with colonies and trading posts established all along the coasts of Europe from the Black Sea in the east to the Codanus (Baltic) in the northwest.

This continued for nearly 500 years, during which a considerable part of the Tribe of Dan emigrated to the colonies. As a result we find, even before 1,000 B.C., settlements of people calling themselves Danites or Danes along the north shore of the Black Sea, in Greece, in northern Italy, in the British Isles and Scandinavia.

This continued for nearly 500 years, during which a considerable part of the Tribe of Dan emigrated to the colonies. As a result we find, even before 1,000 B.C., settlements of people calling themselves Danites or Danes along the north shore of the Black Sea, in Greece, in northern Italy, in the British Isles and Scandinavia.

The great migration of the Danites, however, occurred in the tenth century B.C. when, for some reason, the remainder of the tribe left Palestine in a body. That this migration took place is proved by the fact that Dan is not mentioned in the Roll of Tribes in 1st Chronicles. Dan could not, therefore, have been in Palestine when this record was made. The Jewish writer, Eldad, says that the Danites refused to take part in the wars between Israel and Judah, which resulted from the division of the nation into two kingdoms at the death of King Solomon, and, as a result, “left the country in a body, going to Greece and to Danmark.”

An interesting point concerning the Danites is that when they went to their new home in northern Palestine they immediately named it Dan in honour of their ancestor. Apparently this was characteristic of the Danes for, wherever they went, they left as way marks (place-names) the name of their father Dan. Thus it is that we have the Udon, the Don, the Dnieper, the Dniester, the Danube, Macedonia, Sardinia, the Eridanus (the Po), the Anodanus (the Rhone), the Codanus Sea (the Baltic), Scandinavia, Sweden, and Denmark, to say nothing of countless others in the British Isles.

Thus by their name, their traditions, and their waymarks we know the Danes (Norsemen) were the Israelitish Tribe of Dan.

The Normans

The last of our ancestors to arrive in Britain; as a group, were the Normans who invaded and settled in England in A.D. 1066.

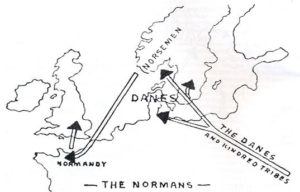

In considering their origin one must begin with a recognition of the fact that, though they came into England from France and though they spoke a dialect of the French language, they were nevertheless not of the French (Frankish) race. They were Norsemen from Norway who had invaded and settled in northern France only 150 years before their invasion of England.

These Norsemen were a northern branch of the Danes. This will be understood if we remember that when the Danish and kindred tribes migrated from the East to north-western Europe, some of them settled in the peninsula called Denmark while others crossed over to the Northland (Norway and Sweden). Those in the Northland, particularly those in the western part of it (Norway), became known as Northmen which in time became Norsemen and then Normans.

In the ninth and tenth centuries many of the Danish people (both South Danes and Norsemen) began to seek new homes. They discovered and settled in Iceland and Greenland, and even went as far as America. A large number of them settled in England and Scotland. Others, mostly Norsemen, proceeded farther south, settling in Northern France, to which they gave the name Normandy, and from which their descendants later invaded England. It is certain, therefore, that the Norman invasion brought no foreign racial element into Britain, for the Normans, being Norsemen, were a branch of the Danes.As the Danes in turn were closely related to the Saxons, it follows that the Normans were racially identical with the Saxons and Danes who had preceded them into Britain.

In the ninth and tenth centuries many of the Danish people (both South Danes and Norsemen) began to seek new homes. They discovered and settled in Iceland and Greenland, and even went as far as America. A large number of them settled in England and Scotland. Others, mostly Norsemen, proceeded farther south, settling in Northern France, to which they gave the name Normandy, and from which their descendants later invaded England. It is certain, therefore, that the Norman invasion brought no foreign racial element into Britain, for the Normans, being Norsemen, were a branch of the Danes.As the Danes in turn were closely related to the Saxons, it follows that the Normans were racially identical with the Saxons and Danes who had preceded them into Britain.

As we have previously established the Israelitish identity of both the Saxons and the Danes, it follows that the Normans, being of the same race, must have had the same origin.

Here an interesting point arises. In our previous studies we have seen that the Danes were Israelites of the Tribe of Dan. Consequently, as the Norsemen (Normans) were a branch of the Danes, it would seem evident that they too were of that tribe. There is an old tradition, however, which says that the Normans were of the Tribe of Benjamin, descendants of those who escaped from Jerusalem when that city was destroyed by the Romans in A.D.70. Whether or not this is true, we do know that part of the people of the Kingdom of Judah, which included the Tribe of Benjamin, was carried away into captivity in Media with Israel. Thus among the Israelites in Media there were some who were of the Tribe of Benjamin and, as the descent of the Saxons and Danes from these Israelites is certain, it follows that among the Saxons or the Danes there must have been some who were Benjamites.

Further, we know that the emblem of the Tribe of Benjamin was a Wolf, and that that is the emblem under which the Norsemen came into north-western Europe. Later, a branch of their descendants settled in France (Normandy) and still later as Normans, many of these moved into England in what history calls the Norman invasion.

It is certain, therefore, that the Normans, being of the same race as the Saxons and Danes, were Israelites, and it seems evident that they were of the Tribe of Benjamin.

The “French” Canadians

In previous articles of this series we noted that the many tribes and peoples from which the British or Celto-Saxon people are descended came into Britain in three main groups, the Iberian, the Celtic and the Saxon; the Iberians and the Celts – the ancient Britons – coming at various times between 1600 and 200 B.C., and the Saxons (Jutes, Angles, Saxons, Danes and Normans) about a thousand years later.

We also noted that, though these groups and tribes came into Britain at different times and under many names, they were, nevertheless, all of one race being but the scattered branches of the Israel or Hebrew people who were being reunited in the appointed place of safety promised to them in 2 Samuel 7:10.

We also noted that, though these groups and tribes came into Britain at different times and under many names, they were, nevertheless, all of one race being but the scattered branches of the Israel or Hebrew people who were being reunited in the appointed place of safety promised to them in 2 Samuel 7:10.

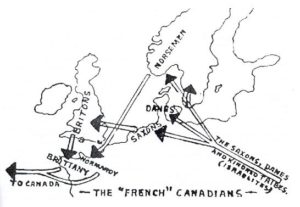

Though both the Britons and the Saxons were thus of one race, the Saxons, coming so much later than the others, were not recognised as brethren and their entry into Britain was bitterly opposed. This struggle lasted nearly two centuries, during which the Saxons gradually drove the majority of the Britons into the western half of the Island and some across the channel to France. Those who went to France settled in an uninhabited district to which they gave the name Little Britain (Brittany) in which their descendants, the Bretons, live to this day.

Racially, therefore, the Bretons of France are identical with the people of Wales, Cornwall and most of western England; their language still being almost the same as the Welsh.

Now let us consider another point. When the several Danish and Saxon tribes migrated from the East to western Europe, most of them settled in the Danish Peninsula and in the lands immediately to the west of it. The others crossed over to the Northland (Norway) where they became known as Northmen or Norsemen. After a time the Saxons (Jutes, Angles and Saxons) invaded and settled in Britain and a little later part of the Danes did likewise. Presently the Norsemen too began to search for a new home and about the year 900 a large body of them invaded and settled in northern France (Normandy). About 150 years later many of these Normans rejoined their brethren the Saxons and Danes, in Britain when they invaded England in 1066.

The next point to note is that there remained in northern France, in the adjoining Provinces of Brittany and Normandy, two groups of people who were not of the French race; the Bretons being Britons, and thus identical with the people of Wales and western Britain, and the Normans being Norsemen of the same stock as the Saxons and Danes from whom the English people are descended. The Bretons and the Normans, therefore, were NOT French; they were Celto-Saxons of the same family and race as the people of Britain.

The importance of this lies in the fact that these Bretons and Normans were the ancestors of the so-called ‘French’ Canadians, it being a matter of historical record that most, if not all, of the ancestors of the French-speaking people of Canada came from Brittany and Normandy.

It is an indisputable fact, therefore, that the French-speaking people of Canada, in spite of their fanatical determination to be French, are not French. They are Celto-Saxons and therefore racially identical with the people of Britain and with the English-speaking people of Canada. As such, they too are Israelites, and only their blind adherence to an alien language, culture and religion, keeps them as strangers among their brethren.

We have presented a small part of that great mass of evidence which proves the Israelitish origin and identity of the British or Celto-Saxon people, and we have seen that their coming into the British Isles in many groups, at different times, and under various names, was but a regathering of the scattered branches of the Israel or Hebrew people in the appointed place of safety promised to them in 2 Samuel 7:10.

Further, we have seen that this scattering and regathering of the Israel people covered a long period of time (from about 1600 B.C. to 1100 A.D.), and that at one time or another during this period one or more branches of the Israel people passed through every country in Europe.

Such a vast migration of people, moving in so many divisions, following so many different routes and continuing for such a long period of time, would inevitably leave many groups behind along the way. Thus it is that there is hardly a country in Europe or western Asia in which we do not find a remnant of the Celto-Saxon race.

These groups are of various sizes, in some countries being only a small fraction of the population while in others they are larger. In a few countries the population is almost entirely Celto-Saxon.

In this latter class are Norway, Denmark, and the Netherlands (Holland). The people of these three countries are racially identical with the people of Britain, being the descendants of those parts of the Cymry, Jutes, Danes, Norsemen, and Saxons, which remained on the Continent when the rest migrated into Britain. Thus, they too are Celto-Saxons, and therefore Israelites and our brethren, and the only thing which prevents their union with the Israel-British Family of Nations is their, and our, failure to recognise our common Israelitish origin.

Important groups of Celto-Saxons also remain in several other countries. In France are the Bretons and the Normans, the Bretons being descendants of those Britons who fled from Britain at the time of the Saxon invasion and the Normans being Norsemen of the same family as the Danes and Saxons.

In France and Spain are several groups descended from those Iberians left behind when the main body moved on into Britain. The Gauls too left some of their people behind in Belgium, France, Switzerland, Spain and northern Italy, and it is evident that some of the people of Sweden and Finland are the descendants of the Danes and Norsemen. It is also evident that groups remain in Germany, Poland, the Ukraine and the Balkans, and it is certain that some of the people of northern Greece and Albania are of the same stock as the Danes and the Scots.

That these, and other smaller groups in Europe and western Asia, are remnants of our race left behind in the great migration of the Israel people to Britain is certain. Now in our day, however, many of these people, by emigrating to Canada, the United States, South Africa, New Zealand and Australia are instinctively returning to their true place among the Tribes of Israel. Such is the identity of most of the so-called ‘foreigners’ among us.

Unfortunately, during the time of their separation they adopted the languages, customs and religions of the Gentile nations among whom they lived and now, though they have returned to the Israel fold, they have brought these alien things with them and in many cases seem determined to cling to them. As a result we have a serious “foreign” problem.

For this is but one solution. It is the proclamation of the fact of our common Israelitish origin and identity, and the prophetic destiny of our race as the instrument of God’s Will and Purpose. Once the ‘foreigner’ recognises these things and as a result recognises that his true cultural and spiritual home is in Israel-Britain rather than in Europe, the ‘foreign’ problem will cease to be.

Courtesy: Canadian British Israel Association