THE BRITISH CHURCH PRIOR TO AUGUSTINE

Courtesy Of ‘The National Message’ 1954 No: 1356 England

HOW many people know that hundreds, possibly thousands, of Christians were murdered in Britain nearly three hundred years before Augustine came here? Very few, one imagines. Yet the historical fact remains. This religious persecution in Britain was the culmination of a vicious empire wide decree of the Emperor Diocletian, who hoped to stamp out Christianity and restore the old pagan religion.

That there were enough Christians in this island to provoke imperial action is obviously a far cry from the persistent notion that Britain owes her Church establishment to the Roman mission of Augustine in the year 597. Nor was the butchery directed against simple isolated groups of believers.

Much more was at stake. Diocletian was determined to eliminate all organized forms of the new faith: and Britain possessed just such an organized Church. In addition to the vast number of Christian martyrs who perished in this island during that year of blood, A.D.304-amongst whom was the saintly Alban-two archbishops, three bishops and an unspecified number of presbyters also died.

Within ten years, however, the British Church had recovered sufficiently to send episcopal representatives to a great international Church Council, at Aries, in the south of France, convened by the Emperor Constantine. Moreover, British bishop delegates attended four such councils before Augustine’s arrival in Britain.

All this unquestionably emphasizes the antiquity of the early Church in this land. Its fame was great enough to claim the distant ear of Tertullian, in Africa. Writing in the year 208, this great church theologian observed that Christianity had penetrated places in Britain inaccessible to the Roman armies. And Eusebius, a third cen tury Bishop historian of Caesarea, in Palestine, tracing the movements of our Lord’s disciples, says: ‘And some have crossed the ocean and reached the Isles of Britain. Gildas, too, adds his voice to the claim for an apostolic origin of Britain’s Church, when he says that many nations, including ‘the island stiff with frost and cold’, received the Gospel light in the last days of the Emperor Tiberius, who ruled at the time when Christ was crucified. Gildas had no notion of any Roman mission, indeed he died twenty seven years before it was sent. Add to all this the comparatively recent testimony of Pope Pius XI, who ‘advanced the theory that it was St. Paul himself and not Pope Gregory who first introduced Christianity into Britain’, and the case for the apostolic founding of the British Church is well established.

Against this vigorous indigenous Church, Augustine was destined to pit his wits. But the much extolled Roman mission was really sent to convert, not the wicked Britons, but the newly arrived pagan Anglo-Saxons. Some of their children seem to have appeared upon the slave markets of Rome, where they attracted the sympathetic attention of Gregory. On his later elevation to the Roman Pontificate he despatched a mission, headed by Augustine, to those Anglo-Saxons who had established themselves in the south of Britain.

The haughty Augustine holds a conference on the hanks of the Severn, A.D. 605,

The haughty Augustine holds a conference on the hanks of the Severn, A.D. 605,

with the Celtic bishops who are seen leaving the conference in sorrow.

The Venerable Bede, himself a Roman partisan, provides a most informative account of Augustine’s high-handed actions towards the British bishops. Sponsored by his friend and patron Ethelbert, King of the Jutes, he made a bid to enlist their aid in an effort to bring all the unconverted of the kingdom into the fold of the ‘Catholic Church’.

Augustine’s natural intolerance was aroused by the irksome discovery that the British Church ‘did not keep Easter Sunday at the proper time besides, they did several other things which were against the unity of the Church… (and) preferred their own traditions before all the churches in the world’. Accordingly, representatives of the Britons were invited to a conference to thrash out the matter.

To this synod, says Bede, ‘there came (as is asserted) seven bishops of the Britons, and many most learned men, particularly from their most noble monastery … to whom the man of God; Augustine, is said, in a threatening manner, to have foretold, that in case they would not join in unity with their brethren, they should be warred upon by their enemies, and if they would not preach the way of life to the English nation, they should at their hands undergo the vengeance of death’. Bede adds, with obvious satisfaction, that ‘all which fell out exactly as he had predicted …. because they had despised the offer of eternal salvation’!

But these were not the least of the Romish band’s troubles. The Celtic Church, centred in Ireland at this time, was also a source of concern to Laurentius, Augustine’s successor. ‘He not only took care of the new Church formed among the English, but endeavoured also to employ his pastoral solicitude among the ancient inhabitants of Britain, as also the Scots, who inhabit the island of Ireland.

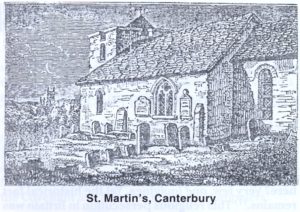

One of England’s lovely old churches, on the site of an earlier building

One of England’s lovely old churches, on the site of an earlier building

which was in existence before the coming of Augustine;

it is said to be the oldest church in England.

This “pastoral solicitude” towards Ireland’s early Church – which had produced such stalwarts of the faith as Patrick and Columba – took the form of a motion of censure from the haughty papal emissary’ In a letter addressed to “our most dear brothers, the lords, bishops and abbots throughout all Scotland”, Laurentius complains: ‘But comingacquainted with errors of the Britons, we thought the Scots had been better; but we have been informed by Bishop Dagan, coming into this aforesaid island, and the abbot Columbanus in France, that the Scots in no way differ from the Britons in their behaviour; for Bishop Dagan coming to us, not only refused to eat with us but even to take his repast .in the same house where we were entertained.

Clearly the early Church in this land viewed with concern the encroachments of the Romanizing party, and the struggle continued until the time of Colman, Celtic Bishop of Northumbria. A show down was inevitable. And when it came, it took the form of a dispute at Whitby in the year 664, concerning the correct date of Easter-this still rankled the Roman party-and ended with the defeat and resigntion of Colman. C 14l The way was thus paved for further Romish indoctrination, a process which continued until the early apostolic Church was smothered and eventually superseded by Roman institutions.

During the period which followed, the Church grew so corrupt, in both doctrine and practice, that it ultimately generated an urge to reform. In startling succession, factions within the Church broke away to renew their stand upon ‘the impregnable rock of Holy Scripture’. And Britain, long since chafing at Roman supremacy, disestablished herself from the Continental Church and returned, during the first Elizabeth’s reign, to her original state of spiritual independence. D.J. C.