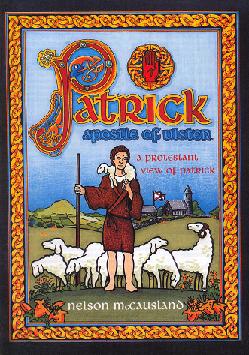

PATRICK, APOSTLE OF ULSTER – (1)

FORWARD

Ireland is a land well known for its myths and legends and this is particularly true when it comes to its ‘Patron Saint’, Patrick.

The Emerald Isle is not unique in this respect. The other ‘Patron Saints’, David of Wales, George of England and Andrew of Scotland fall into a similar category as the mists of time surround them with their own particular myths and legends. Indeed it could be argued that there is more evidence for the place and work of Patrick than for any of them.

Because of the popular pictures and statues of Patrick, with his bishop’s mitre and staff, it is sometimes unwittingly assumed by many that Patrick was part of ‘Roman’ Ireland with his allegiance to the ‘Roman See’. Nothing could be further from the truth and there is little evidence to substantiate such a claim.

It is the function of the Education Committee of the Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland “… to educate the Brethren of our Institution and the general public in the truths and principles of the Reformed Religion, and our historical and cultural heritage.” Accordingly we present this “Protestant View Of Patrick” by a member of the Education Committee, Nelson McCausland, to whom we are indebted for such excellent research and comprehensive writing.

As we present this publication to the general public we are conscious of the desire on the part of many in these days to ‘listen to the other side’. It is our prayer that this publication may contribute to a better understanding of the Culture and Traditions of the majority population of the northern part of this island.

INTRODUCTION

Saint Patrick wasn’t Irish. He wasn’t sent to Ireland by the Pope. He didn’t wear a bishop’s mitre and he didn’t drive the snakes out of Ireland.

Much that is popularly believed about Saint Patrick is simply fiction and fantasy. But what are the real facts about Patrick? What do we really know about him?

Patrick was the son of a British churchman. He was captured by raiders and spent six years as a slave in Ulster. There he was converted and later he escaped back to his home and family. Some years after this he heard the call of God to come across to the island of Ireland and preach the gospel.

His ministry covered the length and breadth of Ulster and through his preaching many became Christians. Churches were built and men of God were ordained to minister in those churches. Patrick was God’s man for Ulster, the Apostle of Ulster.

THE MAN

Patrick was born in Britain towards the end of the 4th century. But what was Britain like at that time?

A Roman army invaded Britain in 43 AD and within a few years they had conquered the lower part of the country. The mountain tribes of Wales and the north held out longer while the Scots were never finally conquered. Hadrian’s Wall still marks the frontier which long ago the Roman legions held against the Scots. Further north there was another wall which was built in 142 AD by order of the emperor Antoninus and was known as the Antonine Wall. This ran across Scotland between the River Clyde and the Firth of Forth. The Romans allowed the Picts to occupy the land between the two walls but the district was reclaimed by Valentian in 368 AD and renamed ‘Valentia’ after him.

Britain was a Roman province, ruled by Roman governors, visited by Roman emperors, colonised by Roman citizens and kept in order by Roman legions. It became almost as civilised and cultured as any other part of the Roman Empire and this continued for 300 years.

A network of roads was developed, stately houses and villas were constructed and garrison towns were built in important centres. The Romans brought with them their religion with its pantheon of pagan gods.

However the time came when the Roman soldiers were needed back on the continent to defend Italy against invasion and Britain was gradually evacuated.

THE ANCIENT BRITISH CHURCH

The Christian faith was introduced to Britain at an early date, probably in the first century, and was firmly established by the time of Patrick.

Tertullian at the end of the second century and Origen about forty-five years later both state that by their time the Christian faith had penetrated Britain. In his book Adversus Judaeos (c 7) he said:

“Britannorum inaccessa Romanis loca Christo vero subdita.”- “Those parts of the British Isles which were yet unapproached by the Romans were yet subject to Christ.”

In 3I4 three British bishops attended the Council of Arles.They were Eborius of York, Restitutus of London and Adelphius, probably of Lincoln. This suggests that by that time Christianity had spread over a large area of Britain. Another church council was held at Rimini in 359 and again a number of British bishops attended. Indeed throughout the 4th century we can trace the steady expansion of Christianity.

PATRICK

Patrick’s original name is said to have been Succat, Patricius being his Latin name.

It is not possible to say with any certainty when Patrick was born but John R Walsh and Thomas Bradley state:

“The conservative dating of about 432-461 for Patrick’s mission and a birth-date c 385, is now … generally accepted” [A History of the Irish Church p 161]

In his letter to Coroticus, Patrick refers to the Franks as still heathen. This indicates that the letter was written between 451, the date generally accepted as that of the Franks’ entry into Gaul as far as the Somme River, and 496, when they were baptised en masse. This places the letter and therefore part of his ministry within the second half of the 5th century.

PATRICK’S FAMILY

Patrick was born into a Christian home and his family had been a Christian family for at least two generations. His grandfather was called Poitus. His father, Calpurnius, was a deacon and a minor local official. There was nothing unusual in this because celibacy was not enforced in the early church.

These names Patrick (Patricius), Calpurnius and Poitus are all Roman names and so Patrick was a freeborn citizen of the Roman empire.

In the Confession as we now have it, Patrick himself makes no mention of his mother. But the author of the fourth Life in Colgan’s collection quotes the Confession as stating that his mother’s name was Concessa. It is possible that an earlier version of the Confession than any still in existence may have contained this information. But an ancient writing On the Mothers of the Saints of Ireland, attributed to Aegnus the Culdee in the 9th century, says that his mother was Ondbahum of the Britons. In the Tripartite Life the story of Concessa was further elaborated and she is said to have been a relative, possibly a sister, of Martin of Tours, thereby linking Patrick with the most prestigious figure of continental monasticism. Jocelin also claims that she was a sister of Martin but such claims are rather late and therefore doubtful.

PATRICK’S BIRTHPLACE

Patrick says that his father owned a farm or villa near the village of Bannaven Taberniae. This is the only clue to Patrick’s birthplace but scholars disagree about its location. Muirchu says that it was ‘not far distant from our sea’ and it certainly makes sense to think of a location close to the west coast of Britain. The Irish raiders would have concentrated their attacks on the western shore of Britain. It is unlikely that they would have raided the east coast and unlikely that they would have penetrated far inland.

In Scotland there is a local legend that Patrick was born at Old Kilpatrick, near Dumbarton. Dumbarton, with its great basalt rock rising up from the banks of the Clyde, was the western terminal point of the Antonine Wall which Antoninus Pius, the adopted son and successor of Hadrian, erected across Scotland about the year 144 AD. At one time this tradition was rejected because there was no archaeological evidence for the existence of Roman villas in southwest Scotland but in recent years evidence has emerged of Roman villas in the Strathclyde region and much academic opinion now favours this as the region where Patrick was born.

However, others look further south and suggest that Patrick was born in Cumbria or even in Wales. The Latin name has been altered by some scholars to read ‘Banna Venta Bernia’ and his birthplace located at Birdoswald, near Carlisile, in Cumbria.

The fact that Patrick’s family owned a villa and had servants suggests that he had a comfortable life and was well provided for during his early years.

5th CENTURY IRELAND

In the 5th century Ireland was divided into a large number of small tribal areas or tuatha. The tuath, which means ‘a people’, was the basic political entity and each of them was quite independent under its elected king. There were about one hundred and fifty of these tuatha in Ireland. However, from about the beginning of the Christian era, there had been a process of political cohesion and eventually the island was divided into five groups of tuatha, known as the ‘five fifths of Ireland’ – Munster, Connaught, Leinster, Meath and Ulster. But at the time of Patrick Ulster itself was divided and there were three independent kings in Ulster.

As regards the history of Ireland in the 5th century very little is known. Professor Gearoid MacNiocaill commented that, “the fifth century has been very justly described as a lost century.”

This view is supported by Professor Charles Thomas who said that, “The fifth century continues to be the most obscure in our recorded history.” [The Living Legend of St Patrick p 121]

In the time of Patrick Ireland had a very small population, around a quarter of a million people. The population of Ulster would therefore have been around fifty thousand. This was a totally rural and agrarian society. In fact there were no towns in Ireland until the arrival of the Vikings. The people lived in ring-forts, crannogs and unenclosed houses.

It is thought that there were as many as forty thousand ring-forts in the island and the most common form of ring fort was the rath. This was a circular open space surrounded by a bank and a palisade. The ring fort enclosed houses and farm buildings and provided some form of protection. The houses were made of wood plastered over with clay and roofed with thatch.

Crannogs are man-made islands in lakes and bogs and they are much less numerous than ring forts. The poorest people lived in unenclosed houses.

Much of the land was covered with thick forests and with bogs. It was the extent of its forests which in early times gained for Ireland the name of Innis-na-Beeva or Island of the Woods. Wild animals roamed freely through the countryside. There were great herds of deer, wild boars with long tusks and even wolves.

The people were a farming people and, as well as the forests and bogs, there were large open plains where they grew crops and grazed their cattle, pigs and sheep. However they supplemented their farming by hunting.

It was a century of turmoil across Europe, as barbarian hordes destroyed the Roman empire and sacked the city of Rome, and the Angles and Saxons invaded Great Britain. This was the start of the Dark Ages but in contrast to this Ireland was comparatively peaceful.

For Ireland the 5th century marked the end of centuries of isolation and the start of the island’s entry into the historical world.

DRUIDISM

Professor James Heron comments: .

“The religion of the ancient Irish was Druidical but the popular idea of that religion is quite erroneous. It included belief in the immortality of the soul and in the doctrine of a day of judgement – doctrines doubtless which, along with others, made them more ready to accept of Christianity.” [The Celtic Church in Ireland p 41]

The religion of the people was Druidism but what exactly was this religion? Among the ancient Celts, the Druids were a class of priests and learned men. They formed an important part of every Celtic community in Ireland, Britain, and Gaul, and their leaders often rivalled kings and chiefs in prestige, if not power. They seem to have served as judges as well as priests, and their counsel was eagerly sought by all classes of society.

It is known that oak trees and mistletoe played an important part in Druidic rituals. It was also believed that there were special powers associated with stone, wood and water. In his History of the Church of Ireland, Bishop Richard Mant describes the ritual which survived to his day and which was associated with a well in county Monaghan. At this place of pilgrimage there was a stone which was reputed to bear the mark of the knee of Saint Patrick, a cross he was supposed to have erected and an alder tree which was said to have sprung up where the saint blessed the ground. The ritual associated with this well involved the pilgrims kissing the stone and placing their knee in the indentation, saying various prayers and bowing to the cross, the stone and the alder tree. When the rite was completed the water taken from the adjacent well would cure sick cattle! Such customs and rituals have survived since pre-Christian times and show us something of the nature of the pre-Christian religion of the island.

It is remarkable that worship which was opposed by Patrick is now associated with him!

SLAVERY

From about the middle of the 3rd century Latin writings make frequent reference to raids which were carried out by the Irish, who were known as the Scotti. Irish traditions also suggest that such attacks took place. In the second half of the 4th century, when Roman power in Britain was beginning to break down, the raids became more frequent. These Irish raiders sailed in curraghs, wooden framed boats covered in hides, which were fast and seaworthy, capable of negotiating the stormy waters of the Irish Sea. As E Estyn Evans said:

“The sea-going curraghs were ideal craft for the Irish raiders who plundered west Britain during and after the Roman occupation: light in weight, of shallow draught and capable of flying over the waves ” [Irish Folk Ways p 237]

Around 400 AD, when he was 16 years of age, a band of Irish pirates raided the countryside where Patrick lived. They hunted down the terrified people and robbed them of their possessions. Some of the people were slaughtered and years later Patrick recalled that:

“They murdered the servants, men and women, of my father’s household”

Others, like Patrick, were taken away by the raiders in their ships to be sold as slaves in Ireland. Again Patrick recalled:

“With many thousands of others I was carried of into captivity in Ireland”

SLEMISH

Patrick was sold as a slave to a man named Milchu who was a Cruithin chief and who lived at Skerry in County Antrim. About five miles away from Skerry across the River Braid stands the hill of Slemish (Sliabh Mis, Mis being a woman’s name). There on the slopes around Slemish, Patrick spent six bleak years as a herdsman of sheep and pigs.

Patrick does not mention the place of his captivity but Slemish in County Antrim is the traditional location of the captivity.

Some recent writers have sought to locate it at Killala in County Mayo. However there are a number of objections to this. Firstly, if this sacred spot had been in Connaught, Tirechan, as a Connaught man, would certainly have set out the claim of Connaught but he did not and in fact he accepted the claim of Slemish. Secondly, one of the obvious objections to Killala is that it is in a relatively flat region whereas Slemish is consistent with Patrick’s reference to a mountainous region. [Confession 16]

Professor Donal Kerr writes:

“Tradition tells us that it was in County Antrim, on Slemish mountain, that Patrick spent six years of harsh slavery. He himself does not name the place but speaks of the snow and frost and rain in mountain and forest; certainly Slemish with its view of the heartland of Ulster was bleak, cold and forbidding.” [Saint Patrick p 5]

Between Slemish and Skerry there is a townland called Ballyligpatrick (the townland of Patrick’s hollow). In it are the remains of an ancient rath.

Patrick was in a strange land, perhaps often cold and hungry, surrounded by a people speaking a language he did not know. But during the years of his captivity Patrick acquired a good knowledge of the local language and also made himself acquainted with the religion, habits and customs of the people. Although he did not know it at the time, all this would be of great advantage to him during his future mission.

CONVERSION

But the most important thing that Patrick gained in Ulster during his captivity was personal salvation.

There on the Antrim hillside, far away from his family, his friends and the comforts of home, Patrick had ample time for reflection. Although he had been brought up in a Christian family, Patrick says that at the time of his captivity he did not know the true God. But the Spirit of God began to work in his heart and his thoughts turned to the God of his fathers.

Paul Gallico expressed it well when he said:

“During this period Patrick found God and God found Patrick and thereafter, to the end of the saint’s days, neither ever abandoned the other. No man ever served God more faithfully, intensely and unswervingly than Patrick.” [The Steadfast Man p 28]

ESCAPE

One night in a dream, six years after his capture, Patrick heard a voice speaking to him. The voice said that there was a ship ready and that in it he could escape.

Patrick fled from his master and made a journey of some two hundred Roman miles which would be equivalent to one hundred and eighty English miles.From Slemish this would have taken him as far as Wicklow, where there is a tradition that a point north of the town was the place of Patrick’s departure. This was a difficult and dangerous journey which took him through forests and across boglands but eventually he reached the port and found the promised ship. Patrick coaxed the captain to take him on board. At first the captain refused but later he relented and Patrick sailed away from the shores of Ireland. He reached land after three days.

To be continued