JEMIMA LUKE

The choir from the village of Blagdon in Somerset dress in the costume of Victorian days,

The choir from the village of Blagdon in Somerset dress in the costume of Victorian days,

the time when Jemima Luke was teaching at the local school. – JOHN HUCKLEBRIDGE

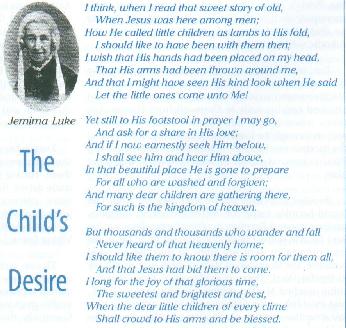

ONE fine early summer morning in 1841, a young English lady filled with Christian zeal was riding in a stagecoach rocking along the country lanes from Taunton to Wellington in Somerset on an errand for her father. There were no other passengers in the coach and, taking a letter from her pocket, she wrote two verses on the back of the envelope, not realizing that one day it would become one of the world’s most popular children’s hymns. She entitled it: The Child’s Desire, but it is better known by its opening line: “I think, when I read that sweet story of old.”

Jemima Luke was born on 19th August, 1813, to an Islington (London) family named Thompson. Her father was a pioneer in several church societies, fighting to take religion to the people and spread the Gospel further than the bounds of the wealthy clergy. He helped found the Sunday School Union, the Sailors’ Society, the first Sailors’ Home and the Home Missionary Society, designed to send ministers out to isolated villages. He was also an active member of the London Missionary Society and regularly entertained missionaries at the family home.

A young daughter, aged three, had died just before Jemima was born, and her baby brother later died at 12 months after contracting pneumonia due to the fashion at the time of taking children out in all weathers without warm clothing or long sleeves. This was supposed to make them hardy! A doctor attended the baby and attached 16 leeches to his chest, but the infant died soon afterwards. Jemima’s mother, who blamed herself rather than the doctor, was never in good health again and died in 1837.

In her autobiography “Early Years of My Life” published in 1900, Jemima recalls a Sunday when she was 10 that was a turning point in her life. She had been caught telling a “fib” and was punished by being isolated from her family. Her father told her she must repent to God, and after a stirring church service, she vowed never to lie again and to live a true Christian life.

Jemima wanted to become a poet and had several of her verses published anonymously in The Juvenile Friend when she was 13. Then she persuaded her parents to let her study under Caroline Fry, a noted writer and editor of another magazine, The Assistant to Education. About this time, Jemima decided to become a missionary to India, to save Hindu girls from early marriages to men they had never met, and degradation by the men’s families. Her father reluctantly agreed to sponsor her as an agent for the London Missionary Society and to pay her passage to India, along with a stipend of £150 a year. However, just before embarking on the voyage, she went down with a virus and her father withdrew his permission for her to leave. She was obliged to return to the family home at Taunton.

Taunton in Somerset with St Georges church in the background – JOHN BLAKE

Upon her recovery, Jemima began visiting a school at nearby Blagdon to teach the children to sing hymns. After writing The Child’s Desire, she taught it to the children and it proved very popular. She set the words to a tune that she remembered children performing as a marching song at a London school. When her father, who taught Sunday School, asked the children to choose her first hymn, they sang The Child’s Desire, and he was so impressed that he sent a copy of it to the Sunday School Teachers’Magazine. Publication of the hymn led to Jemima being offered a job editing a new missionary magazine for children, which contained news from missionary societies all over the country.

Dr. David Livingstone (1813-1874), the famous African explorer and missioner, also contributed pieces. Jemima then became involved in writing for Sunday School teachers on how to tell children about missionary work, and even after her marriage in 1843 to the Revd Samual Luke, a Congregational minister of Orange Street Church, Leicester Square London, (her hymn, in her own handwriting is held by the church) she worked tirelessly to persuade unattached English ladies to go to India to save the Hindu women.

Her famous hymn was published anonymously at first in the Leeds Hymn Book of 1853. Years later, Jemima was asked if she thought it was strange that The Child’s Desire was the only hymn remembered out of all the many she had written. “I do not think it strange at all” she replied, “on the day when I thought myself the only passenger in the stagecoach, I’m quite certain God was there, whispering that song to me!”

Jemima died in 1906, having spent her life trying to be a good Christian and urging others to do the same.

Reproduced by permission from THIS ENGLAND magazine -Autumn, 1995.