SIR ISAAC NEWTON – SUPERMAN OF NATURE

SEER OF THE HIGHER REALM

“God said, Let Newton be! …and all was light.” Could there be a more apparently extravagant encomium than this by Alexander Pope? Yet subsequent generations have confirmed the view. Newton’s theory of gravitation made clear the structure of the universe. It would be better to refer to the principle of gravitation, for though it made its way rather slowly outside England, it was within a century accepted universally as true. The reason for its acceptance was that when tested it was invariably found right. When the theory appeared to be wrong, the solution of the particular problem always turned out to prove Newton right. Newton died in 1727 but in the following hundred years there were striking results achieved by those who adopted his principle. Edmund Halley applied Newton’s techniques to the orbits of comets. Working on the assumption that comets which had appeared in 1531, 1607and 1682 had elliptical orbits and were in fact one and the same comet, Halley computed the future orbit of the comet. It would be affected by the gravitational pull of Jupiter.He predicted that it would return by Christmas 1758. Halley was dead by the time that the comet in accordance with his prediction did reappear. It now bears his name and it was at once understood that the Newtonian principle had received a striking vindication. In the study of the planet Uranus, Sir William Herschel found that its orbit was very erratic. Could gravitation apply only to fairly limited distances? It was found that the perturbances were due to the gravitational pull of another as yet unknown planet. Thus Neptune was discovered.

I cannot enter into the mathematics of Newton’s principle, but his work is of special importance to all Christians, because he was himself a devout believer and in fact left behind him a very large amount of Scriptural commentary. The circumstances of his life are most instructive, especially the fact that his greatest work, the famous Principia (full title Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica) was, as it were, a byproduct of his studies.

A MAN OF THE PEOPLE

Isaac Newton was born in 1642 in the village of Woolsthorpe, about seven miles south of Grantham in Lincolnshire. His father was a small landowner. Needless to remark, there was no indication of genius in the family; but in the case of the highest ability there very seldom is. Isaac was a posthumous child and at first so weakly that he was not expected to live. When he was two, his health improved. As his mother had married again, he was brought up by his maternal grandmother. His schooling was undistinguished and when his mother was again widowed, she recalled him from Grantham school to manage the small family property. How many geniuses have been lost in this way? By the advice of his uncle, the Rev. Ayscough, he was sent to Trinity College, Cambridge. Even then his preparation for the University depended on the willingness of his old schoolmaster, Henry Stokes, to coach him without fees.

Newton had no interest in women, yet is supposed to have been engaged to a Miss Storey when he was eighteen. They did not marry but remained distant friends for many years. His career at Cambridge is somewhat obscure. Owing to the plague in Cambridge, most of 1665 and 1666 Newton spent at Woolsthorpe, the scene of the famous falling apple, always supposed to have suggested the idea of gravitation. It is probable that in these quiet years he did conceive the principle; he also discovered the binomial theorem, the method of fluxions and the theory of colour (connected most probably with his experiments with the prism). He seems not to have been actuated by love of fame, or even by desire to advance the boundaries of knowledge. Pure disinterested desire to know was his guiding motive. That this was so is proved by the manner in which his great discovery was revealed. Three distinguished savants Edmund Halley, Robert Hooke and Sir Christopher Wren – had discussed during 1684 the problem of determining the nature of a planet’s orbit. Halley consulted with Newton who quietly produced the solution along with that of other problems of planetary motion. Halley was enthusiastic and through him the great author was persuaded to publish the Principia in 1687, under the imprimatur of the Royal Society, and that of its President, Samuel Pepys, the diarist.

It would be an insult to the reader to suggest that a brief outline of the book can be successful but a few notes may be helpful. It is probably the greatest scientific work ever written. The medium of Latin was necessary as no other language could at that time have been universally understood in Europe and America. Why it ever ceased to be the language of communication among scholars is an academic mystery. The term “natural philosophy” in the title is used to distinguish a scientific treatise from a work of pure philosophy, i.e. Descartes’ writings. The various physical sciences had not then been separated from philosophy, only subdivided within it.

THE MENTAL GIANT

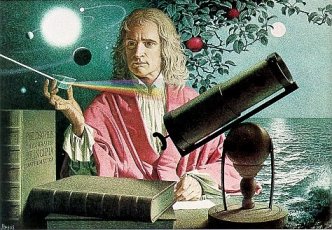

Sir Isaac Newton 1642-1727

The genius who probed into God’s natural works and also into the Bible at a time when Faith was centred around miracles and prophecy

Newton divided the work into three books or sections: (1) concerned with motions of bodies; (2) with bodies which meet resistance; and (3) the application of the basic principles of motion. At the start, he was careful to define his terms – what he meant by mass, momentum and inertia. Then he set out his three laws of motion or axioms. The second book has been especially important in engineering. To the marine and to the land engineer, as to the ship-builder, gravitation with all its involvements has been essential and, of course, continues to be. A recent writer has thus summed up Newton’s achievement:

“He had carefully and soberly analysed the whole universe as it was then known. Using some basic laws of motion and the idea of a force of gravitation behaving in a certain way (i.e. according to the inverse square law) he had accounted for all observed phenomena” (Newton, by Colin A. Ronan, p. 49).

The picture of the universe revealed law, order, precision, a beautiful panorama coming from the hand of God, in Whom this scientist had implicit faith. Hypotheses non Fingo, he declared, by which Newton meant that he did not deal with mere suppositions. It is a pity that subsequent lesser scientists have not followed him.

In the course of his eighty-five years Newton gave much more attention to matters other than scientific. He gave a lot of time to public service; was twice an M.P.(1689-90 and 1701-5).From 1669 to 1701 he was Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge and president of the Royal Society from 1703 to his death. In 1699 he was appointed Master of the Mint*, having been Warden from 1696; during the years 1696-99 the recoinage of the currency was successfully carried through. His knighthood came from Queen Anne in 1705, the first to be given for scientific achievement.

In the midst of what was obviously a very busy life, Newton yet made further researches, on the nature of light and on optics. He was also an experimenter in chemistry, having had his own laboratory at Cambridge.

Of his intellectual eminence it is enough to say that for over 200 years no one found occasion to query his work. Only when astronomy in the present century succeeded in discovering ever farther and farther in the vast depths of space did Newtonian physics appear to require some adjustments. The very highly specialised work of Albert Einstein, whose theories of Relativity are extremely involved, are not properly comprehensible by non-mathematicians. Einstein, it has been said, stands on the shoulders of the greatest scientist the world has ever known. Wordsworth wrote of Newton, “with his prism face voyaging through strange seas of thought alone,” an opinion with which we can agree when we view his statue in the chapel of Trinity at Cambridge. On its base is the just sentence: Newton. Qui genus humanum ingenio superavit.

THE CHRISTIAN SEER

There were other fields which he conquered. This superman of nature was none less a seer in higher realms. In his precious little work on “Daniel and the Apocalypse” he calls 2 Peter “one continued commentary on the earlier work of John.” Thus the Revd T. H. Passmore, himself a seer of the highest order, in the interpretation of the New Testament (St. Peter’s Charter, p. 265). He shows, as Newton had before him, that the Book of Revelation was well known to several writers of the New Testament, one of the greatest proofs of the value of the last book of the Bible, which dovetails in so well with our Lord’s prophecies of the Doom of Jerusalem, and the end of the Jewish Dispensation.

I could not help a certain wry amusement in seeing how the author (Ronan) whom I quoted above, dealt with Newton’s theological studies. He points out that Newton spent more time on theological work than on any other study. Here lay his deepest interest. It is agreed that he gave the same care to this branch of study as he did to physical science.

“Newton’s full contributions to theology are still not fully appreciated since there has been no complete analysis of all his theological notes, as there has been of his scientific ones. When it is realised that he wrote something like 1,300,000 words on the subject, this neglect may not seem so surprising. What is surprising is the immense amount of time and prodigious labour that this figure indicates” (p. 67).

Yes! Strange to the non-Christian or to a “blue bird” clergyman. But the genius who probed into God’s natural works desired to go as deeply into His supernatural works as revealed in His Word. “Such work as he published was considered a most valuable addition to religious knowledge” (Ronan,p. 67).1ndeed! Faith in the later 17th century, Ronan adds, centred round miracles and prophecy.

Now times have changed and not for the better. In looking through the new ecumenically approved Common Bible (based on the 1611 version) I notice that all the run-on headlines of the Authorised Version relating to prophecy in the Old Testament have been omitted. The modern cleric feels about miracles and prophecy as he would towards a disreputable relative; “a real black sheep”. Yet his attitude was foretold by Christ and the Apostles.

“When the Son of man cometh, shall He find faith on the earth?”

Newton was buried in Westminster Abbey. I end as I began with the epitaph which is included in Pope’s works as:

Intended for Sir Isaac Newton. Isaacus Newton. Quem immortaleii, testantur tempus, natura, caelum. Mortalem, hoc marmor, fatetur.

Nature and Nature’s laws lay hid in night. God said, “Let Newton be!” and all was light. To which may be added the great genius’s own words: that he felt like a child on the seashore gathering pebbles from the vast ocean of knowledge.

With acknowledgement to Look Up (Australia)

* While working as Master of the Mint, Newton lived in a house adjacent to Orange Street Church for seventeen years