MUMMIES, TEXTILES OFFER EVIDENCE OF EUROPEANS IN FAR EAST

(Extracted from Science Times – The New York Times – Tuesday, May 7th 1996)

|

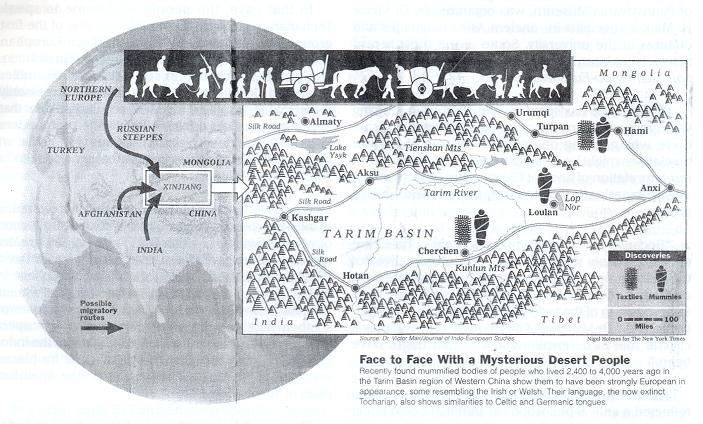

Face to Face With a Mysterious Desert People Recently found mummified bodies of people who lived 2400 to 400 years ago in Tarim Basin region of Western China show them to have been strongly European in appearance, some resembling the Irish or the Welsh. Their language, the now extinct Tocharian, also shows similarities to Celtic and Germanic Tongues. |

IN the first millennium A.D., people living at oases along the legendary Silk Road in what is now northwest China wrote in a language quite unlike any other in that part of the the world. They used one form of the language in formal Buddhist writings and another for religious and commercial affairs, including caravan passes.

Little was known of these desert people, and nothing of their language, until French and German explorers arrived on the scene at the start of the start of the century. They discovered manuscripts in the now extinct language, which scholars called Tocharian and later were astonished to learn bore striking similarities to Celtic arid Germanic tongues. How did a branch of the Indo-European family of languages come to be in use so long ago in such a distant and seemingly isolated enclave of the Eurasian land mass?

More surprises were in store. In the last two decades, Chinese archaeologists digging in the same region, the Tarim Basin in Xinjiang Province, have uncovered more than 100 naturally mummified corpses of people who lived there 4,000 to 2,400 years ago. The bodies were amazingly well preserved by the arid climate, and archaeologists could hardly believe what they saw. The long noses and skulls. blond or brown hair, thin lips and deep-set set eyes of most of the corpses were all unmistakably Caucasian features – more specifically, European.

Who were these people? Could they be ancestors of the later inhabitants who had an Indo-European language? Where did these ancient people come from, and when? By reconstructing some of their history, could scholars finally identify the homeland of the original Indo-European speakers?

Linguists, archaeologists, historians, molecular biologists and other scholars have joined forces in search of answers to these questions. They hope that the answers will yield a better understanding of the dynamics of Eurasian prehistory, the early interactions of distant cultures and the spread of kindred tongues that make up Indo-European, tlie family of languages spoken in nearly all of Europe, much of India and Pakistan and some other parts of Asia- and elsewhere in the world, as a result of Western colonialism.

At a three-day international conference here last month, scholars shared their findings and hypotheses about how the Tocharian language and the Tarim Basin mummies might contribute to a solution to the Indo-European mysteries. The meeting, held at the University of Pennsylvania Museum, was organized by Dr Victor H. Mair, a specialist in ancient Asian languages and cultures at the university. Some of the most recent research has been described in the current issue of The Journal of Indo-European Studies.

Dr Mair, who has spent several seasons in Xinjiang with groups studying the mummies and artefacts, said there was growing optimism that some important revelations might be at hand through genetic studies, a re-interpretation of ancient Chinese texts and art, and a closer examination of textiles, pottery and bronze pieces.

“Because the Tarim Basin Caucasoid corpses are almost certainly the most easterly representatives of the Indo-European family and because they date from a time period that is early enough to have a bearing on the expansion of the Indo-European people from their homeland,” Dr Mair said, “it is thought they will play a crucial role in determining where that might have been.”

The tenor of discussions at the conference also reflected a critical philosophical shift that could affect attitudes toward other research problems in archaeology and prehistory. Most participants invoked without apology the concept of cultural diffusion to explain many discoveries in the Tarim Basin.

For several decades, beginning in the 1960’s, cultural diffusion was out of fashion as an explanation for affinities among widely scattered societies. The emphasis, instead, was on independent invention, and archaeologists were often rebuked if they strayed from this new orthodoxy, which arose in part as a reaction to the political imperialism that often ignored or belittled the histories and accomplishments of subject lands. The Chinese, moreover, had long discouraged research on outside cultural influences., believing that the originsof their civilization had been entirely internal and independent.

But Dr Michael Puett, a historian of East Asian civilizationsat Harvard University, said the research on the Tocharians, the mummies and related artefacts revealed clear processes of diffusion. “Diffusionism needs to be taken seriously again,” he said. Dr Colin Renfrew, an influential archaeologist at Cambridge University in England; made a point of endorsing this view.

Almost a century of studying the Tocharian manuscripts, dated between the sixth and eighth centuries A.D., has convinced linguists that the language represents an extremely early branching off the original, or proto-Indo-European, language. “That’s the working hypothesis, at least for the moment,” said Dr Donald Ringe, a linguist at the University of Pennsylvania.

In that case, the people who came to speak Tocharian might have stemmed from one of the first groups to venture away from the Indo-European homeland, developing a daughter language in isolation. The fact that Tocharian in some respects resembles Celtic and Germanic languages does not necessarily mean that they split off together, scholars said, or that Tocharian speakers originated in northern or western Europe. Tocharjan also shares features with Hittite, an extinct Indo-European language that was spoken in what is now Turkey.

One hypothesis gaining favour is that this scattering of Indo-European speakers began with the introduction of wheeled wagons, which gave these herders greater mobility.Working with Russian archaeologists, Dr David W. Anthony, an anthropologist at Hartwick College in Oneonta, N.Y., has discovered traces of wagon wheels in 5,000 year-old burial mounds on the steppes of southern Russia and Kazakhstan. Many scholars suspect that this region is the most likely candidate for the Indo-European homeland, though others argue for places considerably to the east or west or on the Anatolian plain of Turkey.

The possible importance of the wheel in Indo- European diffusion has been supported by evidence that wagons and chariots were introduced into China from the West.Wheels similar to those in use in western Asia and Europe in the third and second millenniums B.C. have been found in graves in the Gobi Desert, northeast of the Tarim Basin, and dated to the late second millennium B.C. Ritual horse burials similar to those in ancient Ukraine have been excavated in the Tarim Basin.

Linguists concede that their analyses of the ancient language will not produce answers to many of the questions about the Tocharians and their ancestors. Archaeologists are more hopeful, with the mummy discoveries reviving their interest in the quest.

Early in this century, explorers and archaeologists turned up a few mummies in the sands of China’s western desert. One reminded them of a Welsh or Irish woman, and another reminded them of a Bohemian burgher. But these mummies, not much more than 2,000 years old, were dismissed as the bodies of isolated Europeans who had happened to stray into the territory and so were of no cultural or historical significance.

But no one could ignore the more recent mummy excavations, from cemeteries ranging over a distance of 500 miles. Not only were they well preserved and from an earlier time but the mummies were also splendidly attired in colourful robes, trousers, boots, stockings, coats and hats. Some of the hats were conical, like a witch’s hat. The grave goods included few weapons and little evidence of social stratification. Could this have been a relatively peaceful and egalitarian society?

One of the most successful excavators of mummies is Dr Dolkun Kamberi, a visiting scholar at the University of Pennsylvania. He is a member of the dominant, Turkic-speaking Muslim ethnic group in the Tarim Basin today, the Uighurs (pronounced WE-gurs).They moved to the area in the eighth century, supplanting the Tocharians, though Dr Kamberi’s fair skin and light brown hair suggests a mixing of Tocharian and Uighur genes.

His most unforgettable discovery, Dr Kamberi said, came in 1985 at Cherchen on the southern edge of the Taklamakan Desert, an especially forbidding part of the Tarim Basin.The site included several hundred tombs in the salty, sandy terrain. In one tomb he found the mummified corpse of an infant, probably no more than three months old at death, wrapped in brown wool and with its eyes covered with small flat stones. Next to the head was a drinking cup made from a bovine horn and an ancient “baby bottle,” made from a sheep’s teat that had been cut and sewn so it could hold milk.

In a larger tomb, Dr Kamberi came upon the corpses of three women and one man. The man, about 55 years old at death, was about six feet tall and had yellowish brown hair that was turning white. One of the better preserved women was close to six feet tall, with yellowish-brown hair dressed in braids. Both were decorated with traces of ochre facial makeup.

Among the other sites of mummy discoveries are cemeteries at Loulan, near the seasonal lake of Lop Nor and outside the modern city of Hami. Dr Han Kangxin, a physical anthropologist at the Institute of Archeology in Beijing, has examined nearly all the mummies and many other skulls. At the Lop Nor site, he determined that the skulls were definitely of a European. type and that some had what appeared to be Nordic features. At Loulan, he observed that the skulls and mummies were primarily Caucasian, though more closely related to Indo-Afghan types.

In nearly all cases, Dr Han concluded, the earliest inhabitants of the region were almost exclusively Caucasian; only later do mummies and skulls with Mongoloid features begin to show up. At Hami, Caucasian and Mongoloid individuals shared the same burial ground and, judging by their dress and grave goods, many of the same customs.

Scientists have so far been permitted to conduct genetic studies on only one sample, from a 3,200-year old Hami mummy. Although the recovered DNA samples were badly degraded, Dr Paolo Francalacci of the University of Sassari in Italy said that he had been able to determine that the individual had belonged to an ancient European genetic group. He emphasized that the findings were preliminary.

“You can look at the mummy and see it’s Caucasoid,” Dr Mair said. “Now we have genetic evidence. This is an important moment in our research.”

The graves at Cherchen and Hami also produced the most intriguing textile samples from the late second millennium B.C. One of the Hami fragments was a wool twill woven with a plaid design, which required looms that had never before been associated with China or eastern Central Asia at such an early date. Irene Good, a specialist in textile archaeology at the Pennsylvania museum, said that the plaid fabric was identical stylistically and technically to textile fragments “found in Austria and Germany at sites from a somewhat later period, about 700 B.C.“

Dr Elizabeth J.W. Barber, a linguist and archaeologist at Occidental College in Los Angeles and the author of “Prehistoric Textiles” (Princeton University Press, 1991), said that plaid twills had first been discovered in the ruins of Troy, from about 2,600 B.C., but had not been common in the Bronze Age. “My impression”, she said., “is that weavers from the West came into the Tarim Basin in two waves, first from the west in the early second millennium B.C. and then from the north several centuries later.”

Other evidence also seems to point to multiple ancient migrations into the Tarim Basin “While it is clear that the early inhabitants of the Tarim Basin were primarily Caucasoids,” Dr Mair has written, “it is equally clear that they did not all belong to a single homogeneous group. Rather, they represent a variety of peoples who seem to have connections with many far-flung parts of the Eurasian land mass for more than two millennia.”

Whoever they were, scholars said, many of the earlier mummified people were probably ancestors of the Tocharian speakers of the first millennium A.D. But no one knows if those early people spoke Tocharian. As Dr James Patrick Mallory, an archaeologist at Queen’s University in Belfast, Northern Ireland, remarked, the mummies did not die “with letters in their pockets.”

With much arm waving in front of maps, scholars speculated on the routes that Indo-European speakers might have followed into the Tarim Basin. Perhaps the earliest migrants, who looked most like Europeans, arrived from the north and northwest, over the mountains from Siberia or Russia.

Later migrants, Caucasians but with Indo-Iranian affinities, could have moved in from the west and southwest.

After reviewing the many migration theories, including just about everything short of prehistoric parachute drops, Dr Mallory sensed the audience’s growing perplexity. “If you are not confused now, you have not been paying attention,” he said.

One thing seemed clear to the scholars, however. Though East may be East, and West may be West, the twain met often in early times and in places, like the bleak Tarim Basin,that would have surprised Kipling. And these meetings did not begin with the Silk Road, the transcontinental trade route that history books usually describe as opening in the second century B.C. There never was a time, Dr Mair said, “when people were not travelling back and forth across the whole of Eurasia.”

Scholars doubt that these early movements usually took the form of mass migrations over long distances. But after the introduction of wheeled vehicles, pastoral societies could have begun extending their range over generations, coming into contact with others and finding more promising niches far from their linguistic origins.

“For people not in a hurry,” said Dr Denis Sinor, a historian at Indiana University in Bloomington and editor of “The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia,” “the Furasin continent was a very small world indeed.”

In an article on the new research in the Indo-European journal, Dr Mair wrote, “I do not contend that there were necessarily direct links stretching all the way from northwest Europe to southeast Asia and from northeast Asia to the Mediterranean, but I do believe that there is a growing mountain of hard evidence which indicates indubitably that the whole of Eurasia was culturally and technologically interconnected.”

Copyright 1996 The New York Times Company