CHRIST IN NORTH AMERICA? – (I)

Traditions of a mysterious, bearded visitor from overseas have been current across our continent since pre-Columbian times. The universal image of this man, depicted as an influential religious leader, has fascinated me for twenty years, during which time I conducted my investigations among every Native American willing to discuss his or her tribal history with me. Through them I learned that the mythic memory of this light-skinned (often referred to as white-skinned), robed man occurs in ancient myth among numerous Indian peoples.

Traditions of a mysterious, bearded visitor from overseas have been current across our continent since pre-Columbian times. The universal image of this man, depicted as an influential religious leader, has fascinated me for twenty years, during which time I conducted my investigations among every Native American willing to discuss his or her tribal history with me. Through them I learned that the mythic memory of this light-skinned (often referred to as white-skinned), robed man occurs in ancient myth among numerous Indian peoples.

But his story is found most frequently in North American legends, which reveal more information about his appearance and the nature of his arrival. In Middle and South America, he was known, respectively, as the “Feathered Serpent” (the Mayas’ Kukulcan and Aztec Quetzalcoatl), and “Sea Foam”, Kon-Tiki-Viracocha, to the Incas. North of the Rio Grande River, he is generally referred to as East Star Man, Peace Maker, Pale One, Dawn Star, etc.

Native accounts tell of his arrival from the direction of the rising sun, after which he set up a priesthood among his followers, known as the “Wau-pa-nu” (the spelling is phonetic). They were said to have healed the sick and instituted new laws. Blood sacrifice was forbidden and replaced by the use of tobacco, today an important element in all traditional Native American ceremonies. Among many eastern tribes, East Star Man is regarded as the son of the Great Spirit, the Creator.

I first learned of this Son of the Great Spirit from Ricardo Baeza, an Ojibwa medicine man in Golden Valley, Minnesota. He approached me after my lecture about the Michigan Plates. Collectively, they were associated with Daniel Soper and Father Savage, early preservers of a large group of copper artifacts and stone tablets unearthed from numerous mounds throughout the state of Michigan, beginning in the late 1800s.

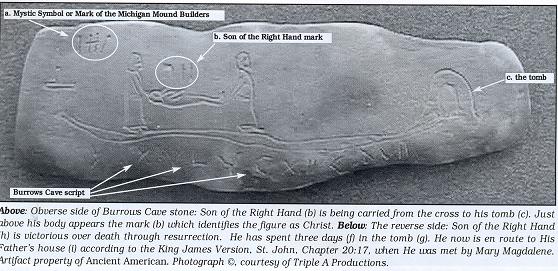

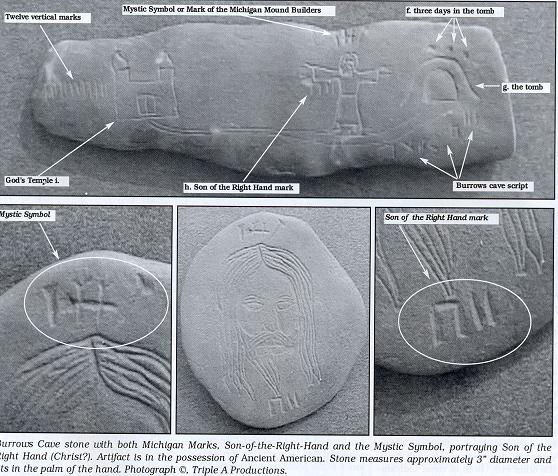

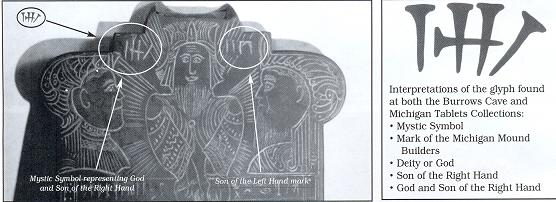

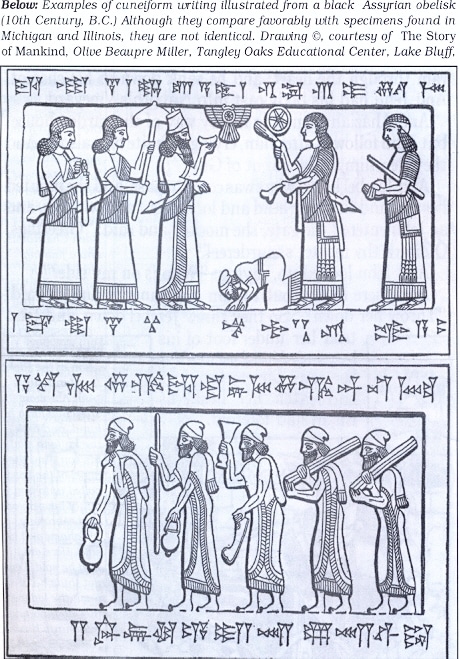

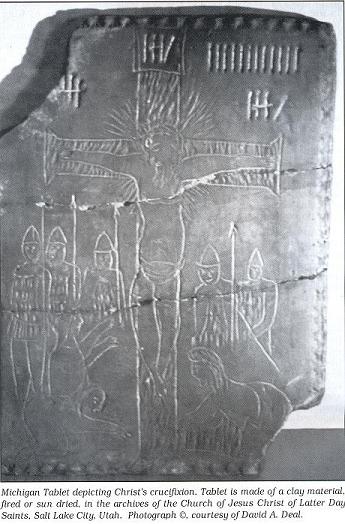

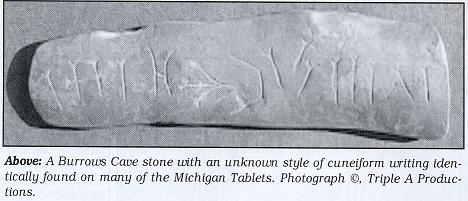

The objects, today scattered across the United States and Canada in mostly private collections, feature portrayals of familiar scenes from mostly the Old Testament and three or more, undeciphered, written scripts, together with depictions of what appear to be persons from Europe or Near East in hostile interaction with Native Americans. Although condemned out of hand as fraudulent by the archaeologists, the so-called “Michigan Plates” or “Soper Savage Collections” continue to intrigue independent antiquarians, who believe the artifacts were made by an Old World religious community in the upper Mid-west during the 4th Century A.D or earlier. In the 1950s, Henrietta Mertz was the first researcher to identify the “tribal mark or mystic symbol” which commonly appears throughout the collection.

Following my Golden Valley slide presentation of the Michigan Plates, Mr. Baeza told me that he could actually read some of the glyphs that appeared on the Soper-Savage tablets, explaining that their symbolic meaning was part of his tribe’s sacred tradition. He added that the so-called “mystic symbol” represented the name of the Creator’s son, pronounced in the Ojibwa tongue (reading the cuneiform characters from right to left) as “Yod-hey-vay”. This name, he said really has an additional syllable, but he fourth is pronounced only once a year in a sacred ceremony and then only by a tribal holy man in the great lodge. Mr. Baeza’s explanation sparked my memory of an article by Ancient American author, David Deal, in Ancient American’s Stone, Clay, Copper, Archives of the Past, March/April, 1994 Issue #5, entitled, “The Mystic Symbol Demystified”.

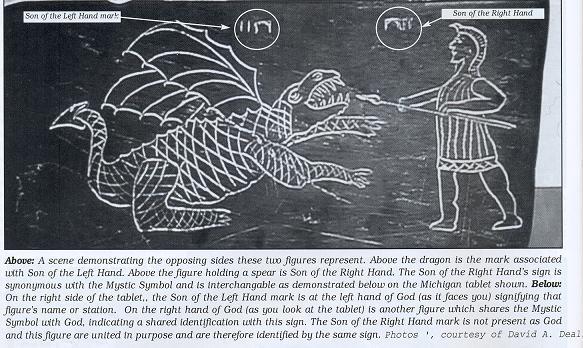

In his investigation of the Michigan relics, Deal was able to convincingly translate from the quasi-Hebrew script the name of two sons of a deity figure featured on the tablets as “Son-of-the-Right-Hand” and “Son-of-the-Left-Hand.” The tablets’ internal evidence unquestionably demonstrate two opposing groups of people represented by two individuals, one good, the other evil. Both of these individuals carry identification marks which appear on many but not all of the plates’ biblical scenes. These well-known moments from the Old Testament clearly identify each sons’ proper role.

For example, on the so-called “creation tablet,” where Adam is apparently brought to life, the Son-of-the-Right-Hand’s mark is included as part of this positive event. But on another plate, where he and Eve seem to be ejected from the Garden of Eden, the Son-of-the-Left-Hand’s mark floats above them, suggesting calamity. This simple but lucid marking of “good and bad,” or “righteous and evil,” is recurring throughout much of the Michigan collection.

On page 18 of his article, Deal writes

“Of course the two sacrifices, one for Yahweh and the other for Azazel (Leviticus 16), are indicative of the two brothers, as well. The stories throughout the Bible of the two brothers from Cain and Abel, Isaac and Ishmael, Jacob and Esau, Manasseh and Ephraim, etc., all point to the same allegory. The fact that the Michigan Christians of the Fourth Century A.D. were aware of this angelic conflict and modern Christians are not, is the major point to ponder.

The modern doctrines would not allow such an interpretation. Of course, not many Christians actually use the name Yahweh in their worship either, but when the New Testament says that the accuser is before the Father daily, making accusations, and that the Messiah is seated again at the right hand of the Father, acting as an advocate, they should, perhaps, reconsider this concept. The point isn’t about to become embroiled in a theological discussion, but to realize that the doctrine pictured on these tablets, does not conform to any Christian religion of this day and age (including 1874). Therefore, the possibility of fraud is diminished to nearly zero, by this fact alone.”

The Michigan relics came to public attention in 1879 when they were reported in a state newspaper. But for thirty one years before, Father Soper had been collecting them throughout the state. From 1848 to 1920, the relics continued to be accidentally uncovered by local people clearing forests and building roads. Over the course of more than seventy years and across twenty seven counties, thousands of slate, clay and copper tablets continued to emerge. Written testimonies and sworn affidavits accompanying many of the discoveries were officially recorded, mostly by farmers who plowed them up while working their land, and not by trained archaeologists, who were neither available nor open-mindedly disposed enough to even give their authenticity the benefit of a doubt. They claimed then, as they still do, that the Michigan tablets must necessarily be fake, because no one from the Old World could have arrived in America before Christopher Columbus.

The Michigan relics came to public attention in 1879 when they were reported in a state newspaper. But for thirty one years before, Father Soper had been collecting them throughout the state. From 1848 to 1920, the relics continued to be accidentally uncovered by local people clearing forests and building roads. Over the course of more than seventy years and across twenty seven counties, thousands of slate, clay and copper tablets continued to emerge. Written testimonies and sworn affidavits accompanying many of the discoveries were officially recorded, mostly by farmers who plowed them up while working their land, and not by trained archaeologists, who were neither available nor open-mindedly disposed enough to even give their authenticity the benefit of a doubt. They claimed then, as they still do, that the Michigan tablets must necessarily be fake, because no one from the Old World could have arrived in America before Christopher Columbus.

Their fossilized mind-set was examined in Ancient American Volume 2, Issue Number 9, May/June 1995, page 31, by Kenneth Moore. He addresses the claims of hoaxing these artifacts by citing the work of two brothers named Scotford, who probably faked a few of their own reproductions of the Michigan tablets. But Moore also points out that although it is reasonable to expect some forgertes with any collection of this size, it must be remembered that when fraudulent duplicates of this kind are made they are usually copied from original artifacts. More revealingly, the first Michigan plates to be found, already in the many hundreds, at least, were already being collected before the Scotford brothers were even born!

By 1920, the scholars of the day had academically crucified several men and women who would not stand down concerning these artifacts. Some colleges and private museums actually destroyed their Michigan tablet collections by casting them into local dumps. In the decades following that wholesale destruction, the Soper-Savage discoveries lapsed into almost total obscurity, and might have been utterly forgotten, save for the independent research of two Amertcan writers, Henrietta Mertz and Milton R. Hunter.

The books of Henrietta Mertz continue to be prized by readers interested in pre-Columbian arrivals in the New World by overseas visitors. Her Pale Ink, an examination of possible Chinese contacts in British Columbia 2,000 years ago, and The Wine Dark Sea, re-thinking Jason and the Argonauts as transatlantic voyagers in quest of a South American Golden Fleece, are still sought after by diffusionists. But Mertz was a professional trained in forgery identification, and it was in this capacity that she was challenged to either prove or disprove the

authenticity of the Michigan tablets.

After 30 years of research, her conclusions were about to go into print, but she passed away unexpectedly before publication. A few years later, her nephew released Henrietta’s Mystic Symbol, Mark of the Michigan Mound Builders. The book argues that the Michigan relics are largely authentic, and urges their preservation as genuine relics from a lost American civilization. During her long years of research, Mertz was able to track down a large number of artifacts originally collected by the Catholic priest, Father Soper. After his death, they had been sent to Notre Dame

University for storage.

In the midst of her investigation, the Father with whom she had been working on the Michigan tablets was coincidentally contacted by missionaries from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, commonly known as Mormons. Aware of their second scriptural book (the Book of Mormon )that testified to the presence of Christ in America, the priest invited them to inspect the Soper-Savage collection. Intrigued, the missionaries wasted no time in contacting Milton R. Hunter of Salt Lake City, Utah, a researcher of American antiquities.

After several months of communication and visits to Notre Dame, the school officials chose to turn over the collection to Hunter rather than Henrietta. She was nonetheless afforded enough time with the artifacts to complete her research for The Mystic Symbol. Elliot Soper, son of Daniel Soper, offered his father’s collection to Hunter after having learned of Notre Dame’s transference of its artifacts.

Hunter’s expanded collection of Michigan plates and related items is today warehoused in the historical archives of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, in Salt Lake City, Utah. Their historical department recently allowed Ancient American staff and Triple A Productions to photograph Mr. Hunter’s collection in its entirety for continued study.

Courtesy: Ancient American Magazine